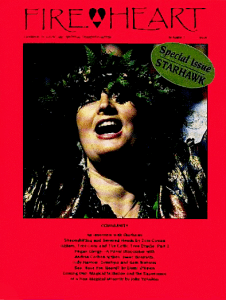

STARHAWK

STARHAWK

Healing Our Wounds ©1993

Since the ground-breaking publication of The Spiral Dance, Starhawk has been the single most visible and influential force in the Neo-Pagan revival. Thousands of people have first learned about Witchcraft from her books and workshops. In fact, the image of Witchcraft as feminist and socially engaged is largely a product of her work. A therapist, educator and activist, Starhawk is also a restless and unconventional spirit. Not allowing herself to be limited by her previous accomplishments, she is constantly growing and looking for new fields to conquer, as she has done in her recently released novel The Fifth Sacred Thing.

In the spring of 1991, Deirdre Pulgram Arthen sat down for dinner at Sabrah’s with Starhawk. Surrounded by the rhythm of doumbeks and the aromas of fine Middle Eastern cuisine, the conversation moved from friends, family, and the novel Starhawk was finally finishing, to world events and the prospects of the Pagan community. After dinner, they retired to the comfortable sitting room of Starhawk’s bed and breakfast for more conversation.

FH: How did you get started in Paganism or goddess religion?

SH: I got started when I was 15 or 16, reading tarot cards back in the ’60s. When I was in college in my first year at UCLA, a friend of mine and I did an anthropology project on Witchcraft. As part of that, we decided to teach a class in the Experimental College on Witchcraft, even though we actually knew nothing about it. We researched it, and when people came in, we said, “Well, we don’t know much about it, but we thought we’d all research and find things out.” Through that, we met some people who were really practicing the Craft, and they began training us. For me, it seemed to articulate and put names on experiences that I had already had in terms of feeling that nature was sacred. I also liked it because I have always had a bad attitude toward authority and this very arrogant belief that nobody else knew more about spirituality than I did. So here was a religion where I, at 17, could study and become a priestess. There wasn’t any other religion I knew about where I could be a priestess. I had been raised Jewish and had been very religious as a child, but in that era, there wasn’t any talk about women becoming rabbis.

FH: It seems that from the very beginning you were teadling. What was the impetus to write The Spiral Dance?

SH: That came several years later. I actually wrote two novels when I was in my early 20s, neither of which ever got published, but one of which won the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Award at UCLA. That gave me a little chunk of money and inflated dreams of glory. So I went off to try to become a writer and travelled around for a year, which was actually a very spiritual year for me. It was a year where I got deeply involved in an everyday practice—meditation, a real commitment to developing that side of myself. The training I had gotten years earlier didn’t go very far because I didn’t go very far with it. I didn’t stick to the disciplines we were supposed to stick to or practice what we were supposed to practice. And at the end of that year—after going to New York and being told that it was very hard to get a first novel published and that I should write some nonfiction if I wanted to be a writer—I started to think about writing something about feminist spirituality. I wasn’t sure at first that it was going to be a book on the Craft, but as I got further into it, that was more and more what it became. So I came back to California and started to teach again and write, although really, to be honest, I still can’t conceive that I actually knew anything at that time to write about.

FH: The Spiral Dance does contain a lot of things that have been really meaningful to a whole lot of people.

SH: It took me about four years to finish The Spiral Dance and get it published, and by that time, I had learned a few things. But I was also close enough to my own beginnings in the Craft that what I tried to put together was the book I wished I had had myself when I was starting.

FH: It’s clearly been very successful.

SH: It really has been. It still is the most successful of all three of my books.

FH: It has provided access for people to the Craft or to feminist spirituality—depending on which approach they’re coming at it from—that hasn’t been done in such a complete way anywhere else. How do you feel about the kind of response that The Spiral Dance has gotten, and the adulation that comes to you as a result of it?

SH: What The Spiral Dance has done, and the fact that people take it and use it and that it has meant a lot to people, is very gratifying to me. That’s been wonderful. That’s what I had hoped for and didn’t actually believe would happen. When you’re writing something like that, especially before you ever get anything published, you think “Is anyone ever going to read this? Is this ever going to make sense to anybody?” So I’ve been very happy about that.

The kind of personal adulation…I don’t know. It’s a paradox to me because it runs counter to everything that I talk about and write about. And it usually doesn’t last very long after somebody actually gets to know me. Someone asked me that question in an interview in San Francisco, and I said something like, “When people get to know me, they find out I’m really the least charismatic person in the world.” And all my friends started taking exception. They said, “Starhawk! You’re not the least charismatic person in the world.” All right, I’m sure I’m not the least. Maybe Dan Quayle is less charismatic.

FH: There are a lot of people who haven’t met you who say, “Starhawk says so-and-so, and that’s the rule,” and all of a sudden, you’re the authority . Most of what you talk about is consensual process, ye! there’s a real perception of you as an authority—or even the main authority—on feminist spirituality and Witchcraft.

SH: My only hope is they’ll get over it some day.

FH: You’ve travelled around the country doing workshops and talks and going to conferences and festivals and all kinds of events. Could you talk about your perceptions of the changes in the Pagan community over the last number of years and also about some of the differences that you’ve found geographically?

SH: The main change that everyone notices so clearly is how much the community has grown over the last few years. It constantly seems to be growing and expanding, with more and more people getting involved and getting interested in this. It’s a broader spectrum of people—not just countercultural or alternative types. When I was in Canada, I did a workshop in Halifax, and 240 women came to it—women who drove six hours from other parts of Nova Scotia from little conservative towns. There’s a tremendous hunger for this kind of thing. In Canada, one of the factors has been the films that Donna Reed made for the National Film Board—Goddess Remembered and The Burning Times. Because they’re National Film Board films, they’re available in Canada for free. You can rent them or check out the videos, and so they’ve become organizing tools.

Reclaiming does summer intensives in Vancouver, Canada and in Michigan the last couple of years. We always try to discuss what the differences are in the Pagan community in different places, and why the different camps have different characteristics. It’s hard to generalize, but I would say that there’s a way in which, in the Midwest, things seem to be more grounded. I like the Midwest. There’s a kind of maturity about it. On both coasts, everyone’s always going nuts about something or other. Things that will require eight days of political discussion and process if they happen on the coasts just get dealt with in the Midwest. In the Midwest and on the East Coast, the festivals seem to be very central to the Pagan community. On the West Coast, things seem to happen more around people’s covens and the circles. In San Francisco, we have a broad enough Pagan community that there are several different, overlapping communities.

We’ve got one that’s centered around Reclaiming that tends to be very political and very involved in a lot of different issues—environmental, peace, feminist issues. Z [Budapest] has a circle centered around her that’s more focused on women’s issues. There are many covens in the Covenant of the Goddess and the old NROOGD [New Reformed Order of the Golden Dawn] covens. There are newer groups that are centered around Pagan networking. It’s nice because it’s a very rich and very multi-layered community. You can go nuts around major holidays if you try to go to every public ritual that is offered. But that had always been my great dream, and maybe we’re lucky that any group is doing any public ritual. Someday there will be more public rituals than you can go to.

FH: Like more church services than you could go to.

SH: I see that starting to happen in other places. To me, it seems that wherever you have a person or a group of people who are willing to take on the task of coordinating things—networking and organizing things—then a Pagan community springs up around it. It almost takes networking and organizing more than somebody who actually knows enough to train or teach anything—just somebody who is willing to pull ritual together, to find a space and put the word out, and something will happen around that.

Another thing that I’ve seen in the last couple of years is this move to sober up. A lot of people are involved in 12–step programs, dealing with alcoholism and food addictions and co-dependency. That, I think, is hopeful, too. The people that I know who have been involved in those programs just become much easier to get along with. A lot of the interpersonal crap that we run on each other in groups that saps our energy somehow seems to fall away and not drive us quite so crazy.

FH: Do you think that 12-step or recovery-oriented programs are part of a maturing within the community, a willingness to look at yourself in a certain kind of way, an attaining of adulthood in some way?

SH: I think so. It’s also, of course, happening outside the Pagan community, but I do think that it’s part of our maturing and part of our ongoing healing. You come into the Pagan community—most of us weren’t born and raised in the Pagan community—with a whole lot of wounds. We live in a society that’s constantly inflicting wounds, so we need healing, and I think as we heal, it will help our images of community.

FH: Do you feel that the Pagan community attracts people who might have more wounds to heal and more healing to do because of the kind of community it is and its accepting nature?

SH: I don’t think that there is any community that isn’t full of people who are wounded by this culture because we come out of a society that basically doesn’t value us. I think the Pagan community attracts people who are willing to look at their wounds. And that heals them.

FH: How did Reclaiming start? Where did it come from, and what does it do?

SH: Reclaiming started about 10 or 11 years ago when one of the women in my coven and I decided to teach a class together. We’d gone through years, in our coven, of struggling around power issues and finally felt that we had achieved a nice flow of power in the. group.

We wanted to see if there was a way for other groups to start from there, rather than having to go through all the painful work we had done. So we thought we would teach in pairs as a way of modeling that kind of flow. We put together a six-week course based around the four elements. Each week we’d do another of the elements and the training that was associated with it. The fifth week we did the center, and the sixth week was a ritual that the class created. Our idea was that, throughout the class, we would hand on as much of the class as we could to the students, so that by the end, they were creating their own ritual and teaching their own class. It worked very well. It worked so well that they demanded a follow-up class, and we had to put together something else. By the time we finished that, they wanted a third class, so we started to rope in the other members of our coven to teach. Then we got some of the graduates of our three classes to student teach with us, and before we knew it, we had an ongoing program.

We had to put the word out about these classes somehow, so we started sending out flyers that one of the women in our group who’s an artist did. It got more and more elegant. Then, since it went out in a little newsletter, we started to put out a newsletter ourselves. We also thought we should do public rituals for all these people, and we began doing that. A couple years into it, we were doing a big public ritual for Samhain based on this ritual we called the Spiral Dance ritual, which we’d done for the first time in 1979 when The Spiral Dance book came out. It’s quite elaborate and involves a lot of rehearsals and a chorus and costumes and all kinds of things. Right before that was happening, a bunch of us went down to Diablo Canyon to start up a blockade to try to prevent them from starting up this nuclear power plant on an earthquake fault. We were down there for three weeks, and that was when we really got exposed to doing direct action that was organized in affinity groups and run by consensus. Meanwhile, all these other people were left to coordinate the Spiral Dance and do all the stuff that we’d been doing. By the time we came back, our little coven had expanded into a collective, and that collective is still going on with quite a few of the original people and, fortunately, also with a lot new people.

Of course, we’ve been through all kinds of things through the years. When we first started, in the spirit of complete openness and equality, we had long collective meetings where we decided every single thing by consensus, and they were open to anyone who wanted to come. It was a nightmare. We finally had to find some diplomatic way to say, “No actively hallucinating psychotics in the meeting, please.” We had a retreat, and at the retreat, we realized that we needed to have some boundaries, that we really couldn’t work together and have a sense of safety unless we actually knew who was in the collective and who wasn’t. So we closed the collective and tried to figure out who was in it and who wasn’t. We worked out a structure where we had different small groups to take on certain projects. We said, “What shall we call these groups?” and somebody said “cells.” We all laughed and thought it was funny, but that is what we’ve ended up calling them ever since. That way, the cells could meet, and the newsletter cell could decide things like what color paper to print the next issue on and which articles to put in and which to edit out, and the whole collective didn’t have to be involved in all of that. The teacher cell could figure out what classes we’d teach. That’s really the way that it functions, and it’s functioned pretty well.

Like any group of volunteers, it has its ups and downs and its times of terrible, gross inefficiency. But over the last few years, we’ve been getting it together a little bit better on the practical plane. Also, when you get a whole group of intuitive, witchy types who are great at doing magic and great at teaching magic, but who can’t add or subtract, it’s very difficult to get organized. But we’ve worked at that. We’re now in the process of trying to get our own independent, nonprofit status as a religious organization. We’re actually solvent. We worked out a rhythm where the collective meets about four times a year as a whole collective, and the individual cells or working groups meet as often as they need to, to do whatever projects they do. We teach regular classes in the Bay area. We publish the newsletter. We do a lot of public ritual. and we do summer intensives, which I’ve already mentioned.

The summer intensives are wonderful and a very good way to get yourself steeped in all of this, taking a week to work on your abilities in your magical practice. We’ve now been doing a summer intensive for five years outside of Vancouver. We’ve tried, over the years, to train people in other areas to teach, so we’ve taken on student teachers from the Vancouver area, and this year we’ll be taking on some from Portland. Last year, we instituted a teachers’ track for people who wanted to work on their skills at teaching magic. This year some of them will student teach with us. Some of the student teachers who have trained in years before will now become full teachers, and over the years, we hope to bow out of it altogether—maybe going on to do something somewhere else—and leave behind a community with a number of people who are capable of training and passing these things on to other people.

FH: You’ve got your model of going to one place and building it up there, and then leaving and doing it somewhere else. What do you think of the idea of setting something up in a more permanent location where people could come and get that kind of training?

SH: I would love to do that, and I’ve often thought about doing that in California—of being able to sit still, stay home and let people come to us. There’s also a limit to what you can do in a week, no matter how intense you get. It would be wonderful to be able to have people come and study for a year or two years. To become a rabbi, it takes four years of rabbinical school after college. That’s a dream that I have for the future. I think it’s still a ways away, and I’m not sure that I’m the one… I would like someone else to set up the school where I live. I could just teach there. The running of it and the organizing is … Vickie Noble has been trying to do something similar with her mystery school in the Bay area. She was talking about the organizational headaches and the immense amount of work that it takes. But I do think that would be good for us to have, and a place where scholarship around the Goddess could be carried on. Carol Christ was talking about trying to campaign to raise money to endow a chair at Harvard in Goddess studies. Goddess studies and Paganism should be given that kind of respect in the academic world. But there’s always a part of us that says, “No, we like being outlaws.”

FH: That’s a question. There’s this quickly growing community of people who are coming and reading whatever they can get their hands on, taking workshops and going to festivals, not necessarily hooking up with a teacher or a group and not having access to in-depth training.

SH: There are a whole lot of questions that are tied up in that, like the question of paid clergy. Is that something we would want as a community? How would the clergy function? I’m not sure clergy is the right term, but having people who actually could make their livelihood by teaching and training and organizing things, which, in a sense, a few of us do. I’m able to do that because of the books I’ve written. Some people manage to do it, but to ask people to commit several years of their lives or a year of their life to some kind of educational process—in this society, it usually leads to some kind of work, a career in terms of making a livelihood out of it. I think eventually the community could support that if we decided that we wanted to support that. There are good arguments on both sides.

There’s something really wonderful about the structure where everyone who wants to can set up their own coven, and nobody takes money for doing it. You do it in your living room, and you don’t need an institution behind you.

FH: You said that’s where a lot of your joy in first finding the Craft came from.

SH: But on the other hand, there’s also something wonderful in being able to perfect your skills around your joy. Maybe you never perfect them, but to be able to develop them. When we’ve done big performance-oriented public rituals—like two years ago when we did the Spiral Dance ritual for over 1,000 people—it became almost a full-time job for me for about two or three months. I somehow got into both doing a lot of the kind of artistic direction and doing a lot of the grunt work like phone calling and coordinating. I could afford to do that because that was my writing time.

FH: Well, whether you could afford it or not is a question.

SH: It would be wonderful to be able to support somebody to do that who might otherwise be working some kind of job that they’re not too thrilled about, and to have more of that kind of thing happening. Plus there’s a lot that we could be doing for kids, now that we have more kids—from some kind of education to producing some written materials for kids, to summer camps—all kinds of things that other religions have for their kids. At a certain point, you need more than just volunteer energy, because when everything is run by volunteers, it’s hard for people to make the kind of commitment to it—to have the time and have the accountability that somebody does when it’s their livelihood, when it’s their main work.

FH: We talk about the Pagan community like it is a real community that exists, and at the same time, it seems like a big, anarchic group of people who just happen to bump into each other for some reason or other. Do you think that we’re moving in any kind of direction that would allow those things to happen in the Pagan community?

SH: I would guess that, within the next decade, at least some of the sub-communities of the Pagan community will move in that direction. I think there will be enough people who do want it that they will create it for themselves—one way or another. In some ways, CUUPS is kind of a whole new aspect of the Pagan community. I don’t know if we’ve joined them or they’ve joined us, but there it is. They’re much more hooked into an institution that’s already functioning, so they may be able to provide some of those things through alliances with the Unitarians. The Unitarians have already produced this wonderful study material—”Cakes for the Queen of Heaven” has taught a lot of women and men about the Goddess. They’re working on one now that is multicultural, and they have someone working on curricula for kids.

FH: With a specifically Pagan focus?

SH: It’s nature-oriented, Earth-oriented. So there may be other resources out there we can draw on. But I think there will also always be people who don’t want to have anything to do with institutions, don’t want to be institutionalized, and I don’t think the Craft or Pagan community will ever lose that. I hope it never does. Even if we do have some people who are the paid community organizers and administrators, people still will be free to form their own circles and start their own groups.

FH: I can’t imagine a time when anyone would try to tell anyone else what we should all do .

SH: It wouldn’t get very far.

FH: No, it wouldn’t. Nobody would listen. How do issues in such spheres as politics, feminism and ecology get handled in Reclaiming? How do the very politically active and the less politically active in Reclaiming work together?

SH: Within Reclaiming itself, we have a spectrum of people from those who aren’t terribly politically active to those who are hysterically, continually politically active. Reclaiming itself, as an organization, doesn’t do anything overtly political.

FH: If you’re applying for religious incorporation, you can’t really.

SH: But we don’t need to. If we want something political to happen, people who want to do it simply form a new group to do it. What Reclaiming has done is provided training in ritual and in the Craft to a lot of the Pagan community in the Bay area, and a lot of the people who are involved in political work in the Bay area have an interest in Paganism. So it’s been a resource pool for skills for people to develop. I think it has had an influence on the style of some of the politics, direct or indirect. San Francisco also has its own style, so the marches there tend to be full of masks and costumes and giant figures and stilt-walkers and drums, all kinds of drums. They’re good old-fashioned peace marches, but they have all these other elements of ritual naturally in them.

FH: It must be wonderful to have that natural blend. On the East Coast, I don’t think it happens the same way.

SH: I think the blend works out pretty well. We try not to try to put a lot of pressure on everyone in the Pagan community to go out and do our style of politics, but rather, we try to be resources for people who want to learn and want to do things.

Around the Gulf War, there was a big Pagan response. The Reclaiming people and the people that are in the loose anarchic Pagan community were very involved in and active and out there marching and out there in the streets doing civil disobedience. Many of us are also nonviolence trainers, and we offered nonviolence training to the larger community. Glenn Turner at Ancient Ways held meetings for Pagans about conscientious objection. There was also a big march of over 100,000 people, and we pulled together a Pagan contingent and had our banner that said “Witches Against War. ”

At the same time, there are other people who are not that active in those kinds of politics, but who spend a lot of time and energy on organizing the Pagan community and doing things like interfacing with Christians and dealing with fundamentalists and educating people about the Craft. I feel deeply grateful to those people for taking that on because that also needs to be done. In some ways, I’m just as glad that they’re not organizing all the same things we’re organizing.

FH: Do you ever get impatient with people who are into Paganism as a fun thing to do or as a fulfilling spiritual practice as a participant, but who aren’t involved in creating change or taking an active role in political interface—or with people who are involved in politics but not involved in any hifld of spiritual process?

SH: I get annoyed sometimes with things I hear people say, but what I hear most often from people who aren’t involved in trying to make change out there is that they are too overwhelmed by dealing with their own stuff. They’re working so hard at healing their own pain, their own childhood or whatever has happened that they don’t have the energy left to get out there. I think that the rituals and the things we do can be very meaningful to people and help people feel a sense of their own power. I think that people naturally do get involved in the larger society around them and change it. I don’t mind the political people themselves. If they don’t feel any call to do something spiritual—that’s fine. Maybe their spirituality may be expressed through their politics. I always prefer that people who don’t really feel like coming to a ritual don’t come to ritual.

What does really irritate me to hear, and I hear it often from certain political people, is, “Well, isn’t all this spirituality just a way of avoiding being involved in politics?” It has a little hook. I start to rant and rave and scream and fume and list the number of times that I’ve been arrested for something. Often I hear that coming from people who define themselves as political, who have an intellectual ideology that they hold to, but who aren’t themselves involved in doing a lot of action.

FH: Not everyone can respond by pulling out how many times they’ve been arrested, though.

SH: Also, getting arrested isn’t necessarily the mark of how politically effective you are or how committed you are, either. But I think if you looked at the Pagan community as a whole and if there was a way, first of all, to count it—which there isn’t—and then count how many of those people are involved in some kind of related political activity around environmental issues or peace issues or feminist issues or something, compared to any other religious community (except possibly the Unitarians or the Quakers) you would find the level of involvement of Pagans is enormously high. Again, when we do our summer intensives, we usually do a session that’s just networking, where people go around and say what they’re involved in. I’m always amazed at the level of commitment and the things that people are involved in in those groups, ranging from running battered women’s shelters to education with men around domestic violence to working to preserve old growth forests to work around AIDS issues. It just goes on and on. It’s very exciting to be working with these people.

FH: Going back to family issues and kids, what are your observations about the way that children and people witli children are having an impact on the Pagan community? Are there any particular roles that families have in terms of what they bring to the community?

SH: A change has happened in the last few years—the great Pagan baby boom. There are just a lot more kids and people with kids in the community. I think it’s wonderful and healthy if we want to survive as a community and as a world, as a planet. I think we’re lagging behind in providing some of the supports that parents could use and their kids could use, but I hope we will catch up.

In our own community, parents have pushed us to be more aware of things like providing child care at public event sand space for kids to be in. Often, kids really like to come to rituals, and most Pagan groups are pretty open to kids participating.

FH: One thing that I’ve noticed is that kids’ participation changes the nature of some rituals because you can’t have some of the same kind of quiet space or expect it to be silent. Have you seen any conflicts arising with people who don’t want children imposed on them?

SH: Sometimes there are those conflicts. There are so many different needs. What we try to do in public ritual—some of them are more suitable for kids than others, and sometimes parts of them are more suitable than others—is to provide child care with the understanding that the kids can be in the ritual as much as they or their parents want them to be, but there is a place for them to be taken care of if it’s too much for them or if they get too much in the way of the ritual. Sometimes, if we have quiet time and trance work, the parents will have somebody who will take the kids off and tell them stories, or if we’re working in small groups, we will have a small group of kids. Sometimes that works and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes the kids don’t want to go with the other kids. They want to be with their mommies. They want to be with the grown-ups. But usually it works pretty well.

FH: Part of it depends on how old the kids are.

SH: We try to have some rituals that are specifically for kids. One of the women in Reclaiming does a kids’ Winter Solstice ritual that’s oriented toward the younger kids, but some of the older ones go along anyway for the fun of it. It involves baking Solstice cookies and decorating them like the sun and having the grown-ups tell them stories. They get a floating candle, which they can light before they go to bed on Solstice night and then wake up in the morning and blow it out. Then the rest of us are up all night doing the ritual.

FH: That’s a wonderful way of including them while recognizing what their limitations are.

SH: We try to include the kids, but we don’t force them to take part in the ritual. So many Pagans had so much other religious stuff forced on them that we tend to bend over backwards not to make any demands on our kids. Sometimes I wonder if that’s really wise, if it might not be better to say, “Look, you need to respect the space of the ritual and make a choice either to be in or be out,” when they’re old enough to understand. There are a lot of ways we can teach and train kids, especially if you start when they’re really young, so that they can grow up with these kinds of structures coming very naturally to them.

Some of our kids have really challenged us. One of my friends had a long talk with her daughters when they were around 7 and 10 about how you just can’t tell everyone that mommy’s a Witch. You need to be cool about this and not talk about it in school. Her younger daughter got absolutely furious. She said, “Why shouldn’t we talk about this in school? How are we going to get it to Reagan if we can’t even talk about it?” She came in with a dollar bill one day absolutely enraged, saying, “Look at this! It says ‘In God We Trust.’ How come they get to put their god on the money and we don’t even get to talk about ours?”

FH: That’s a very good question.

SH: It is a very good question. And then you start to think about it, and you say, “Yeah, how come?” Should we accept that we have to be so quiet and careful, or should we perhaps be out there demanding our rights?

FH: One of the things people talk about in raising Pagan children is the conflict between schools and home. What do you do about privacy about what you do at home and the need not to tell people outside? Doesn’t that create a dysfunctional family for the kids, and how do you resolve it? One way to resolve it is not to keep it a secret.

SH: Of course, a lot depends on where you are in the country and what your job is. One of the reasons I do so much talking and writing and shooting my mouth off about what we do is because I can be out there. I am out there. You create a safer climate for other people to gradually come out to.

FH: About you and your own personal direction. Do you see yourself doing the same kinds of things you’re doing now ten years from now? What do you want for yourself, as opposed to your wishes for the public and world change and those sorts of things?

SH: That’s a good question. The last few years since writing Truth or Dare, I’ve been writing fiction. I thought I was writing a novel, but actually I was writing, I think, at least two novels, at least one of which I hope to complete this year and get it out there. That’s been something I’ve wanted to do, that I really like. I may ultimately go back and forth between writing nonfiction and fiction. I swore after Truth or Dare I wasn’t going to write anything that required footnotes for at least another decade. But once I’ve finished with these two books, I think I’ll be ready to take a little break from fiction.

I’m also hoping to have a child of my own. That, I’m sure, would change my life enormously. I can’t even begin to imagine it, or I’d think better of the whole thing. I’m pretty much content with my personal life. I like my house. I like living collectively. I like living in the city. I like writing. I’m very fortunate that I’m basically able to do what I want in terms of my work. I have enough money that I don’t have to worry about it. I guess I’m sort of attached and ingrained in my present lifestyle. My partner and I are trying to decide things like should we live together and, if so, where. I don’t want to move out of my house. Is there room for anyone else? Where are we going to put the baby if we have a baby? But those are things that I’d like to resolve at some point.

One of things we’ve been doing over the last couple of years is working on some collaborative, multi-cultural rituals, and that’s something I hope to do more of—to build those alliances and make them stronger, and build alliances with more of the Native people. There’s a lot of education to be done there on both sides. I think people in the Pagan community are wide open to Native American spirituality but don’t always understand that there’s a responsibility implied with that to support the struggles that Native people are involved in right now—really crucial land rights issues, which are also crucial environmental issues, issues around seeing the land as sacred. There are ways that we could be a strong support for them. Certainly, many Pagans have already given a lot of support for these things. And I think there’s education to be done in the Native American community about respect for our traditions, too. It’s a very delicate issue. On the one hand, we’re part of a similar kind of religious tradition that has been very strongly suppressed and has suffered.

On the other hand, we are mostly white people with white privilege and all that that implies. Our tradition, while very similar to Native American ways, is a lot looser than Native American traditions. We’re a lot more free-form, and we don’t necessarily appear on the surface to be as serious or as long-standing. So this kind of alliance building has to be done with a lot of tact and understanding and a willingness to let go of a lot that they’re not too comfortable about, with dignity. It can be very fruitful. The other thing that I feel more and more strongly about the next ten years is that we’re in for some major environmental crises. We’re already having them in California. We’re in the fifth year of drought, and people are still talking about drought continuing and climate change and what that’s going to mean. What will it mean if the rains don’t come back. Now after five years, our reservoirs are down to 30% of normal. They’re cutting off water for many of the farms and for agriculture. This is the edge of global warming. Everywhere I have been in the last five years or ten years, the weather has always been strange, and it just gets stranger and stranger. In the last year or two, things like the cutting of the old growth forests and some of the incredibly destructive projects done in the name of progress have been going on at an incredible rate. It takes so much land and energy. It’s such a tragic waste that instead of taking the resources we’ve got left and trying to develop some sane use of our energy toward Earth’s needs, we’re just throwing them all into weapons and shooting them into space. Wasting them. I feel very concerned about what’s happening to the Earth.

FH: What keeps you going? What nourishes you through all the activism, through the putting out and the giving and the teaching and the working for change? What takes care of you?

SH: I live in a very supportive environment, and I have a very supportive community around me. There’s something about having other people who are involved in the same things, who you know you can sit around and watch TV and scream and cry with and throw things with that’s very supportive. It’s made a tremendous difference to have circles of people who feel the same and who aren’t afraid to express their feelings about anything. My household is involved in a lot of the same projects that I am, or in similar things, so we all support each other and learn from each other.

I have a really wonderful, supportive partner, which is new for me. For seven years now, I’ve had involvements with people, but not something serious. Finally, last summer around the Summer Solstice, I had a long talk with the Goddess and I said, “Look, I can’t go on being the High Priestess of the sacred, erotic Goddess and not get any myself. The least you could do, really, for someone who works as hard for you as I do, is to turn up with a decent lover for a change, because otherwise I am going to burn out.” It may have been that, or maybe it was sitting on the wishing stone at Avebury making a wish. According to my friend’s 7-year-old daughter, a very important part of this ritual is having your picture taken at the stone. But something or other finally worked. That has made a big difference in my level of optimism and energy.

FH: It sounds like something that you’ve really been a part of creating, like the idea of the sustainable community that you talk about in Truth or Dare.

SH: I’ve worked hard to create that in my own life. It’s really been worth it. And doing ritual—it works. It gives you back a lot of energy. And for me, just being in contact with nature is sustaining, too. It’s one of the things that’s been the hardest for me this year. I really love California, and I feel very energetic about the land and the plants and the animals that live there. Usually I can always get energy just going out on a hike or going out to the mountains, but with the drought, it’s been really terrible. You go out to the mountains and everything is so dry. You feel the pain of the Earth, and it’s dying all around you. The places I usually go for that kind of nourishment just make me feel more and more sad and worried.

FH: What is your vision for the future of the Pagan community? What is your wish?

SH: What I see happening in the next decade is that society, as a whole, is going to really look again at this question of what is “the sacred.” The Pagan community, along with Native spirituality, has a very clear and very needed answer: that the sacred is the Earth—the air, the fire, the water that’s embodied. It’s here, and you’ve got to respect it. You’ve got to protect it. What’s really different about us and the larger culture is the larger culture’s belief that what’s sacred is outside the world somewhere. That, to me, underlies a lot of these other issues about what to do with our forests and do we cut down the old growth and should we wage war in the Middle East. Should we provide medical care for the disadvantaged, care for people who have AIDS? If we say the sacred is the body, if we say “Goddess is us,” then we have to protect the Earth, then we can’t pollute our waters. We have to have a sane way of using our energy. We have to take care of our people—people who are sick, people who have completely messed up their lives. We have to provide for them because they are, in some way, also the Goddess. We can’t continue to resolve all our problems by force and by violence. We have to find other ways of resolving our differences. I see that as the underlying philosophical debate, and I think it’s going to be a hot debate in the coming years. There are a lot of strong feelings on both sides.

I don’t think that the dominant culture is going to roll over easily, so I think that we will see the Pagan movement growing enormously. Along with that, we’re going to see a need for more institutions to support that growth: education, stuff for children, some sort of professional organizers or clergy or facilitators. We’re probably also going to see a strong backlash from fundamentalists. We shouldn’t let that make us paranoid and afraid, but we shouldn’t be surprised.

My wish for the Pagan community is that we could really raise these issues outside of our own community as well as within our own community—not to proselytize, but to make people aware that there is another way of looking at things and that it’s very crucial, very vital to our survival. My wish would be that we could raise them in a way that will be listened to, that we could make some changes in the old world culture—a real shift in priorities—and put the Earth at the top of our list of priorities as being the Goddess.