EarthSpirit

EarthSpirit

Report on Religions for the Earth and the People’s Climate March, Part II

Published December 31, 2014 by EarthSpirit Community on EarthSpirit Voices

Written by Andras Corban-Arthen

This is an end-of-the-year report (in two parts) on my participation in some interfaith activities this past fall. Brief commentaries about these events were previously published on EarthSpirit’s Facebook page, and a version of this report appears in the latest issue (#119) of Circle Magazine. I’d like to thank all the members and friends of EarthSpirit, whose generous donations to our community support our participation in events such as the ones I describe here.

The Climate March on Sunday was doubtlessly the best-organized demonstration I have ever been a part of. The organizers had anticipated at least 100,000 people, so they had staggered the marchers by dividing us into several different contingents, “penning” each one in a different city block adjacent to the March route. The contingents were defined by “themes” which identified different ways in which people related to climate change: science, for instance, or politics, or religion/spirituality, etc. That way, you could identify whichever theme you were most drawn to, go to that particular city block, and wait with like-minded people until it was your contingent’s turn to start marching.

The Pagan Environmental Coalition of NY led by Courtney Weber, which took on the job of organizing the pagan marchers, wisely had us join the interfaith contingent, and we shared the street with Buddhists, Muslims, Quakers, Jews, Christians, Hindus, Unitarians, Bahá’ís, Sikhs – it was like a mini Parliament of the World’s Religions in the guise of a block party. A Muslim group brought along an inflatable mosque. A Christian group built a Noah’s Ark float to focus attention on how animals are imperiled by global warming. About twenty EarthSpirit members showed up – not only from New York, but from Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Jersey as well – bringing drums and rattles, and getting all kinds of people to join in singing many of our community’s chants.

The PECNY also helped to put together an interreligious service to kick off the March, and they were very kind to invite me to offer the pagan blessing in the ceremony. These are the words I spoke:

“In the Spirit of the Earth, we are coming together;

in the Spirit of the Earth, we are one…” *

We come from the north, and we come from the south;

we come from the west, and we come from the east.

We gather from all directions

to march for this living planet

who is our home, who is what we are.

But we do not march only for ourselves,

we march for all beings of the Earth.

And so we call to sun, to wind and rain;

we call to mountains and glaciers;

we call to all who walk and crawl, who fly and swim;

we call to our ancestors, both seen and unseen;

we call to oceans and streams,

to trees, and grasses and stones

to guide and bless every step we take,

that we may once again live in harmony

with our Mother the Earth.

As it was, as it is, as it ever shall be;

with the flow and the ebb, as it ever shall be.

(© 2014, Andras Corban-Arthen; *© 2000, Deirdre Pulgram-Arthen)

By the time my turn came, the crowd had grown to approximately 10,000 people packed like sardines in our block; there was barely enough room to move but a few inches. From my vantage point up on the stage, I was suddenly able to see what those below me couldn’t: just one street away, an unending river of people was flowing along the March route – a surprising and breathtaking sight. I certainly hadn’t expected anything quite that massive; it was quite obvious that there were substantially more than 100,000 people marching.

Just before we finally started to move, I got into a conversation with one of the police officers patrolling our street. He told me that, in his thirty years on the force, this was the first time that the event organizers had more than delivered on what they’d promised. According to him, demonstration organizers tend to grossly exaggerate beforehand the number of people they expect at their events, in the hope of generating enough excitement to actually draw something close to that number. This time, when the organizers had first predicted around 100,000 marchers, there had been a great deal of skepticism among the authorities and the media; except that he had just heard over the police scanner that the line of marchers was over four miles long, and that the current estimate was around 400,000 people. But what really impressed him the most, he told me, was that there had not been a single arrest or similar incident of any kind reported, and that, amazingly, the marchers were not leaving any trash at all in their wake. “Tell you what,” he said, “if what I’m seeing here is what this movement is really about, then I gotta think that maybe there’s still hope for the world.”

Report on Religions for the Earth and the People’s Climate March, Part I

This is an end-of-the-year report (in two parts) on my participation in some interfaith activities this past fall. Brief commentaries about these events were previously published on EarthSpirit’s Facebook page, and a version of this report appears in the latest issue (#119) of Circle Magazine. I’d like to thank all the members and friends of EarthSpirit, whose generous donations to our community support our participation in events such as the ones I describe here.

Two important and related events were held in New York City over the weekend of the autumnal equinox, 19-21 September: the People’s Climate March, a 3-mile long demonstration through the streets of Manhattan as a call for awareness and action regarding environmental deterioration; and the Religions for the Earth Conference, held at Union Theological Seminary to bring together some 200 leaders from diverse spiritual traditions, to discuss how teachings of the various religions can address the climate change crisis. I attended both events, which were timed to coincide with the Climate Summit scheduled to take place a few days later at the United Nations, at the behest of Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.

The Religions for the Earth Conference was organized by the Union Forum, a platform within Union Theological Seminary which promotes dialogue about religion and social ethics in order to bring about positive civic engagement. In her message of welcome to the conference participants, Karenna Gore, director of the Union Forum, had this to say about the purpose of the event:

“Spiritual and religious leaders have a place in this conversation precisely because it is their vocation to call for sacrifice and reverence to something larger than oneself. Religious leadership is at its best when challenging the status quo, including the powerful, wealthy institutions and individuals who will resist being moved. Our religions are organized differently, but each has the potential for exponential effect throughout our interconnected world. Those of you gathering at Union this weekend hold extraordinary strength within you and also the kindness and love to bring out the best in each other.”

I attended Religions for the Earth representing the three main organizations with which I am affiliated: my community, EarthSpirit; the Parliament of the World’s Religions, which was one of the co-sponsors of the conference; and the European Congress of Ethnic Religions, of which I am president. The Parliament’s delegation also included our Chair, Imam Abdul Malik Mujahid, our Executive Director, Dr. Mary Nelson, and several other trustees, among them Phyllis Curott, the other pagan who serves with me on the Parliament’s Board.

Most of the presentations at the conference took the form of panel discussions, in which participants from several different religious traditions addressed topics such as “Climate Change, Gender & Human Rights”; “Integrating the Earth into Worship, Liturgy and Devotion”; “Environmental Racism and Climate Justice Initiatives”; “Engaging Ecological Despair and Grief”; and “Race, Class & Hemisphere: Regional Identity and Climate”, among others.

I was asked to be one of the members of a panel entitled “What Moves Us: Values, Narratives & the Climate Crisis – the Indigenous Traditions”, moderated by Tonya Gonnella Frichner of the Onondaga Nation, and founder of the American Indian

Law Alliance. The other panelists were François Paulette of the Dene people from northwest Canada, Mindahi Bastida-Muñoz of the pueblo Otomí from México, and Chief Arvol Looking Horse of the Lakota Nation. My role on the panel was to represent the indigenous European traditions. I had met most of the other panelists at previous interreligious events, so I was very glad to be in their company once again.

One of the most important points made by everyone in our panel was that the environmental crisis has grown out of a prevailing sense in Western culture that we are separate from the Earth, which fosters in people the entitled delusion that we can treat the natural world any way we want to. In my own remarks, I pointed out that, in Western culture, this sense of separation has specifically been fostered and transmitted by the dominant religion. The notion that Nature is fundamentally base, and eventually destined to be replaced by an otherworldly paradise (or its opposite) has been a deeply-ingrained Christian paradigm for many centuries. The same is true for the notion of a divinely-appointed human

supremacy over all other beings of the Earth: the human arrogance and greed, and the objectification and devaluing of Nature that are such predictable corollaries of that notion, lie at the very core of the environmental disasters we are now facing.

Our discussion also underscored the fact that, for many decades, indigenous peoples have been issuing warnings about growing changes which are affecting climate and, therefore, everything that exists upon the Earth; but Westerners have not listened, because they are in the habit of dismissing anything which indigenous people might say.

This point was likewise made, in eloquent fashion, by the Onondaga faithkeeper Oren Lyons during one of the plenary sessions. Chief Lyons told about a meeting he once had with an Inuit elder from Greenland, who informed him that “the ice is melting in the North” – trickles of water had begun to appear on the surface of the glaciers some years before, and those trickles had now grown into permanent rivers. Throughout the rest of his speech, Chief Lyons ended every new paragraph by repeating the warning that “the ice is melting in the North”; the more he said those words, the more that he powerfully drove home the sense of urgency, and even of inevitability, surrounding climate change. Some people in the audience were visibly flinching. As he was about to finish, Chief Lyons revealed an alarming detail he had been saving for the very end. That speech we had just heard, he told us, was not new; it was, in fact, the exact same speech he had delivered at the United Nations fourteen years before. But no one had listened then, he admonished us, and it had taken the U.N. almost a decade and a half to finally organize a Climate Summit.

Because participation in the conference was by invitation only, and limited to just a couple of hundred attendees, it fostered a sense of intimacy which I have rarely found at other interfaith events, and provided the opportunity for rich, in-depth dialogue. I think that many of the conversations and initiatives that emerged from Religions for the Earth will prove to be very fruitful over the next several years. The conference ended with a deeply meaningful multifaith service at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, with former Vice-President Al Gore as one of the main speakers.

Indigenous spirituality, EarthSpirit Community – An Interview with Andras Corban-Arthen

Published April 22, 2014 by EarthSpirit Community on EarthSpirit Voices

Interview by Christopher Blackwell

When we think of the Pagan religions of Europe, most of us consider the original religions long dead with only the reconstructions that exist today. But is that actually true? Did the old religions die out completely or did they hang on as folk lore, or did any of them manage to survive into the modern age? Here is one area that we might ask of Andras Corban-Arthen, who is the founder of EarthSpirit Community, one of the oldest Pagan groups still operating in our country.

When we think of the Pagan religions of Europe, most of us consider the original religions long dead with only the reconstructions that exist today. But is that actually true? Did the old religions die out completely or did they hang on as folk lore, or did any of them manage to survive into the modern age? Here is one area that we might ask of Andras Corban-Arthen, who is the founder of EarthSpirit Community, one of the oldest Pagan groups still operating in our country.

Christopher: Could you give us a bit of background on yourself as a person?

Andras: My family of origin is Hispanic. On my father’s side they were mostly from Galiza, in northwestern Spain, which was the last outpost of Celtic civilization in that land. Though they have lost the original language, most Galegos to this day still consider themselves to be Celts, and that was an important part of the cultural context in which I grew up. My mother and her father were Cuban; her mother was Basque.

I grew up in Spain, in Cuba, in Florida and in Puerto Rico. We were living in Havana at the time of the Revolution, but left soon after; we were planning to go back to Spain, but things didn’t work out and we came to the U.S. instead. I was raised Roman Catholic, and spent a few years in a special school for boys whose families had destined them for the priesthood (I can still recite a lot of the old Tridentine Mass in Latin by memory), but I parted ways with Christianity when I was sixteen.

I’ve traveled a good bit, mostly throughout Europe and the Americas. I came to Massachusetts in the late sixties to go to college, and have lived here ever since – first in the Boston area, then for the past fifteen years in the countryside of the Berkshire hills, toward the western part of the state. My wife Deirdre and I have been together since 1980, and have a son and a daughter, ages 24 and 20. We are part of an intentional pagan family, about a dozen of us who’ve been together for close to three decades now.

We live in Glenwood, a 135-acre working farm surrounded by thousands of acres of forest, which also serves as a pagan sanctuary and small conference center. Over the years, as a way to honor our relationship with this land, we’ve built a stone circle, a 60-foot-wide labyrinth, an Ancestor Shrine and a Peace Cairn. There are a lot of maples on the land, so we make our own maple syrup, and we have an organic garden that yields most of our produce for the year. We have lots of domestic and farm animals (dogs, cats, goats, sheep, chickens, turkeys, ducks, rabbits and a llama) and the land abounds with all sorts of wildlife. And we have a wealth of spiders.

As for what I do, I serve as spiritual director of the EarthSpirit Community, through which I’ve been full-time pagan ‘clergy’ since about 1980. My main work involves teaching, public speaking, community development, spiritual counseling, organizing events, officiating at ceremonies such as weddings and other rites of passage, and interacting with the media.

A good deal of my work has also been focused on interfaith dialogue and networking, particularly through the Parliament of the World’s Religions – I am a member of its board of trustees, and am currently coordinating its Ambassadors program, as well as serving as liaison to its partner organization in Guadalajara, México. I am also on the board of directors of the European Congress of Ethnic Religions, an organization headquartered in Vilnius, Lithuania, which promotes the revitalization of indigenous European paganism, and in which I serve as international interreligious liaison. And I am part of the advisory council of the Ecospirituality Foundation, an NGO based in Torino, Italy, which works with the United Nations on indigenous issues throughout the world.

Christopher: How long have you been Pagan? What path do you follow?

Andras: Officially, since the beginning of 1969, which is when I met my teachers. They were a married couple, about twice my age, who were part of what originally had been a Gaelic-speaking family from the Scottish Highlands (the man in the couple still spoke Gaelic fluently). The family had been forced to leave their homeland during the Clearances, and some of them eventually settled near Edinburgh. At the time I met the two of them, they had been in the Boston area for some time, pursuing graduate studies, though they eventually moved on.

I was told about them by a mutual friend, who, before agreeing to introduce us, pointedly warned me that they were ‘witches.’ That really piqued my curiosity, because the thought that there might actually be people in the late 20th century who considered themselves to be witches seemed so outrageously absurd to me that I had to check them out.

But they turned out to be quite different from what I’d expected – they were very intelligent and well-educated, but also very accessible and unassuming, and we hit it off right away. Our first couple of encounters included several remarkable ‘coincidences’ on both of our parts that left us with the sense that our meeting was somehow fated.

For me, it was definitely one of those things where you meet someone and you immediately feel like you’ve known them all your life, like they’re family. In particular, the things they told me about their spiritual practices somehow made far more sense and were more immediately appealing to me than anything else I had found. After a few weeks, as we started developing a friendship, I asked them if they would teach me, and they agreed to do so. I’ve been engaged in those practices ever since.

Christopher: Is this neopaganism or is there a tie to the ancient religions?

Andras: Their teachings were not neopagan, although, at the time, I had no way of knowing that, since I had no other frame of reference except what I was being taught. But several years later, after my teachers left the area and I was on my own, as I started to meet more and more neopagans it became disconcertingly obvious that what I had been taught was very different from what my new friends practiced.

One major difference is that neopaganism typically borrows isolated elements from many diverse cultures and creates a very eclectic synthesis of them.

Conversely, what I was taught came from one particular culture which was indigenous to a very specific part of the world; and the fact that I was not a member of that culture by birth or rearing, and that I was not being taught those practices in the land where they had originated, were both obstacles to my assimilation of the teachings, and there were certain compensations that I had to make to overcome those obstacles.

For my teachers, the idea that you could just take random bits out of a culture into which you hadn’t been assimilated didn’t make any sense – they thought it was like eating the skin of a fruit while leaving the pulp to rot.

There were many other important differences: for instance, my teachers’ practices were essentially animistic – they involved no belief in or worship of deities. At the core of their teachings was the experience of Mystery, of engaging the unknown directly, without attempting to explain it or shape it. Rituals (if they could really be called that) were very simple and mostly wordless affairs, which relied more on the execution of practices than on anything else – the kinds of ‘dramatic’ ceremonies that are so common in neopaganism, including the enactment of various mythological tableaux and such, played no part at all in what they did. We didn’t work in a circle, or invoke elements, or use specifically ‘magical tools.’

Most of their practices were meant to be engaged in a state of trance, which they had several different ways of attaining. The Gaelic term they used for ‘trance’ essentially means ‘mist’: you became ‘enmisted’ – in other words, you engaged a process that took you outside the ordinary world and, in so doing, gave you access to spiritual currents that enhanced you, and changed you, and shaped you. One of the ways they used for inducing the trance was communion with a particular mushroom – this is yet another difference, since many neopagans see such practices as dangerous or inappropriate.

All of their teachings were rooted in a sense that the natural world was the matrix, the source of life and spiritual wisdom and soul-strength, but to them, nature meant wilderness – environments that were not manipulated and controlled by humans. So we spent a lot of time in the woods, mostly outside the city, though there was a particular park near us that was pretty much abandoned and reverting to its natural state, where we could go in a pinch.

This is another way their teachings differed from neopaganism, in that they were adamant that I strive to experience the natural world as it really was, not as a symbol. In neopaganism, there’s a very common pattern of representing nature symbolically, as various aspects of the human condition (air is intellect, fire is passion, water is emotion, etc.) My teachers stressed the very opposite: in their approach, for instance, not only was fire never passion or any other human trait – it wasn’t even fire. To them, the very concept of ‘fire’ was itself a symbol that kept us from truly experiencing the essence of the force we call by that name. Some of their practices were meant to induce a state in which language became meaningless, and where the natural world could be perceived much more directly.

Because of my youth and lack of experience, while I was with my teachers it never really occurred to me to probe too deeply into the background of what they taught me; I pretty much accepted it at face value and focused on the practices themselves. My encounters with neopagan groups, which had such a different approach, made me want to get a more objective sense of what I had been taught. A couple of years after my teachers had left, an American Indian friend suggested that the teachings I had received from them might be the remnants of an indigenous (or, as he put it, ‘native’) tradition from the Highlands, and that some of the practices sounded very similar to shamanism.

So I started to read up on shamanism (this was many years before it became a New Age fad, so the information was not easy to come by), and that led me to a wider study of indigenous cultures. After a while, it became very clear to me that there were certain key elements which were consistently found among indigenous peoples throughout the world, and that those very elements were strikingly similar to a lot of what I had been taught. And then I realized that the old pagan cultures of Europe took on a whole new perspective – a richer, fuller meaning – if they were looked at in the context of indigenous traditions.

I also began to wonder that, if indeed, what I had been taught represented a survival of an indigenous pagan tradition – could there be others? Where could they be found? How might they be similar or different? So, I set myself the task of attempting to find out the answers to these questions.

Christopher: When we think of the old religions, most of us consider that they disappeared after the coming of Christianity. How could any of them survive, and in what form, into the modern age?

Andras: It’s hard to answer this briefly, because it’s a very complicated subject and not well-served by brevity or generalizations, but I’ll give it a try. Yes, conventional wisdom certainly holds that the old pagan traditions disappeared as a result of the Christianization of Europe, but one of the main problems with conventional wisdom is that it tends to get passed along unchallenged and untested. There’s a subtle but important distinction, for instance, between something ‘disappearing’ and something ‘ceasing to exist.’ It’s very clear that most of the pre-Christian European spiritual traditions have disappeared, because they’re not obviously present, not easily found. And, of course, it’s a good bet that most of them have also ceased to exist altogether. But was that actually true for all of them? How can we know that for sure?

It is quite well documented, for instance, that the Mari people in Eastern Europe have maintained their unbroken animistic pagan religion to the present, even after the Christianization of their country several hundred years ago. Could there be any other similar survivals elsewhere in Europe? Is it possible that some of those old traditions may actually have survived by ‘disappearing,’ by going underground?

I have now spent over thirty-five years trying to find such survivals, and it’s been a very difficult, painstaking process involving lots of correspondence, lots of phone calls, lots of travel. In that time I’ve met many people, both in Europe and in the Americas, who had practices that were obvious syncretisms of Christianity with traditional pagan elements, to varying degrees. Those are not that hard to find – you scratch the surface a bit, and there they are, far more common than perhaps many imagine.

I’ve tried to focus my search, however, on finding people who were preserving what I would consider unbroken, substantial survivals of traditional paganism – such as the Mari – that were as untainted as possible by Christianity (to the degree that anything in Western culture, including neopaganism or even atheism, could be ‘untainted’ by Christianity at this point). This has been a much more difficult process, because it has involved not only finding such people and making contact, but more importantly, gradually cultivating enough trust to get to the point where they were willing to meet with me and to answer some of my questions.

To date, I have found close to a dozen, in both Eastern and Western Europe. That’s not a lot, but if I’ve been able to find those with my relatively meager resources, I imagine there must be quite a few more out there.

I should make clear that these survivals are not widespread or out in the open. They mostly involve very small, isolated communities or even just a few families, whose practices and beliefs are either not known to most of their neighbors, or are tolerated by them. And they are not people living in little thatched huts, wearing medieval peasant garb, though their way of life tends to be substantially different from modern American urban culture.

The survivals I have found have certain key elements in common that I think have helped them to endure: They exist in fairly remote or ‘undesirable’ rural locations, in places where the original, ancestral languages are still spoken; this has provided them with a certain degree of insulation. They are in regions where there have been major sociopolitical upheavals which have destabilized the existing power structure and have taken the focus away from religious persecution or suppression.

They involve extended families or small communities that hold on to a very strong cultural identity and nationalistic sentiments, and particularly deeply-ingrained feelings of connection for the physical environment in which they live, and their ‘religions’ are very much an integral, vital part of their culture; in other words, they are not just trying to preserve their religion, but their entire way of life. And they involve people who bear a strong animosity – in some cases, hatred – toward Christianity, for reasons which range from the cultural and historical to the purely personal.

The people who preserve these traditions claim – as my own teachers did – that they are unbroken, that they have existed as far back as anyone can remember (in the sense of cultural, not individual memory, naturally). It is, of course, almost impossible to conclusively prove any of this because, first, any attempt to offer irrefutable proof would require them to expose themselves to public scrutiny, which they’re not at all likely to do, as it would mean giving up perhaps the most important thing that has allowed them to survive in the first place; and, second, most of them quite probably lack the kind of detailed documentation that would be needed for such proof to be truly conclusive.

Obviously, there’s a lot more that could be said about all this. For the past several years, I have offered a presentation entitled “The ‘Indians’ of Old Europe” (a title which was given to me by a Hopi elder), describing in greater detail some of my experiences, limited though they be, exploring the perspective of the old pagan cultures as indigenous traditions, as well as my efforts to find current survivals of them. I’m hoping to be able to offer it in book form by next year.

Christopher: When and why was EarthSpirit Community formed?

Andras: I founded EarthSpirit in 1977, originally as a bartering co-operative, in an attempt to start developing community by finding people who shared some of my own interests in nature spirituality, social activism and radical politics. When my wife Deirdre came along in 1980, we decided to turn EarthSpirit into a much more comprehensive and specifically pagan type of organization.

When I began meeting my first neopagans, one of the things that I found particularly confusing was that they were presenting paganism exclusively as a religion. My sense, based on the teachings I’d received as well as my own research, was that the old paganisms had not been stand-alone religions but, rather, cultural traditions that had spiritual practices and beliefs deeply integrated within them. To me, it seemed that in the interrelationship between culture and religion, the culture served as the vehicle through which the spiritual principles and values were incorporated into the everyday lives of the people.

But, if paganism was going to exist as a religion without a culture, how was it going to achieve that integration? The answer, it seemed clear, was that the automatic default would be mainstream American culture, which is inherently Christian (even in ways that are not so obvious) and seemed to embody the very opposite of the ideas and values that most neopagans I knew were professing to uphold. (Personally, I think that this particular conflict, and the resulting lack of integration, have only gotten worse over the years, and that they’re the source for a lot of the problems which so many modern pagans frequently complain about.)

So, as we envisioned EarthSpirit, we felt very strongly that its chief aim should be to help develop modern pagan culture and community – even if it had to be of a generic nature in order to include all of the people we were trying to reach – that could gradually help to identify traditional pagan values and eventually incorporate them in people’s lives.

In 1979, the year before Deirdre came, I had organized the first Rites of Spring gathering under the sponsorship of the Mass. Pagan Federation, a networking organization of which I had been one of the founding members. Unfortunately, as has happened with so many other pagan confederations over the years, the MPF disbanded right after the gathering, so Deirdre and I decided to continue organizing the event (which is now approaching its 34th year) [ed. note: ROS 36 will take place next month] under the aegis of EarthSpirit.

From then on, things began to develop very quickly. Our initial focus was to provide services for pagans in the Greater Boston area, so we began to offer public classes in various locations, as well as open seasonal rituals, various kinds of special-interest groups, a newsletter, a monthly coffeehouse, an ongoing study group, retreats, speakers, a film series, salon-style discussion groups, etc.

As the organization grew in numbers, we also began to acquire members from all over the Northeast, and eventually from various parts of the country. In response to our growing membership we added three more gatherings, began to publish a professionally-produced magazine, and developed our ritual performance ensemble, MotherTongue, which has performed nationally and internationally, and has produced several recordings. I also began to travel around the country a good bit, speaking at various conferences and offering presentations which were sponsored by some of our national members.

With the coming of the Internet, our numbers grew even more and we started getting members from other countries as well. This was around the same time that some of us moved to Glenwood, so our work evolved to yet another stage as we developed a website and an Internet presence, and began to offer programs and ceremonies at our new home. We developed Anamanta, which is a pagan spiritual practice adapted from the teachings I received, in an attempt to make them more accessible.

We also established several programs for young people, including EarthWise, a pagan summer camp, and EarthSpirit PeaceJam, a service-learning group for adolescents in collaboration with the PeaceJam Foundation, a wonderful organization that brings teen-agers together with Nobel Peace Prize laureates to develop projects around themes of social justice, peace, the environment, etc.

Obviously, work of this kind and scope is not something that one or two people can do by themselves. There’s a whole core group – well over a hundred of us – who work together to run the organization and manage the events. But it’s not just a question of how many, but also of how long – a lot of our core group has been involved in this work for ten to twenty years or more. I also think that we have been able to last as long as we have because for so many of us, what we do for EarthSpirit is part of our spiritual practice – whether we’re cooking a meal, teaching class, or putting stamps on fliers. And we are blessed to be part of a community that includes a lot of very creative and talented people – and generous, to boot: there’s no way we could do most of what we do (particularly our interfaith outreach) without their ongoing support.

One of the most rewarding things about the work we do is when that work gets shared and spreads throughout the community at large. For instance, I was just reading a new book, “Universal Heartbeat: Drumming, Spirit and Community,” by my friend Morwen Two Feathers, who is a long-time member of EarthSpirit, and I couldn’t help but reminisce on how things were in the old days. Back in the mid-seventies, when I was first exploring shamanism, I started to use a drum in my practices as a way to induce trance, and found it extremely effective. But when I took it to a couple of rituals organized by Wiccan friends, I got all kinds of flack about it because, after all, the drum was not a tool listed in the Book of Shadows.

At the first Rites of Spring, I was the only one there with a drum, and I built a small fire and invited people to take part in a fire circle, but most everybody just sort of moved away, as if they were afraid of catching something. I remember somebody joking that if I wanted to play Indian, I should find a loincloth and take my tom-tom to the reservation, because “we’re pagans here.”

Eventually a couple of belly dancers joined, and a tambourine player, and someone playing a recorder, and that was the first fire circle at Rites of Spring – pretty pathetic, though ultimately meaningful. But every year after that, we kept having a fire circle, and it grew, and more pagans brought drums. And then people like Morwen and her partner Jimi, and many others made huge contributions to the evolution of the fire circle, until it became not only a centerpiece of the culture at Rites of Spring, but also was spread around the country by some of our community members, and now there are several Fire Circle gatherings in various parts of the country that are directly descended from the one at Rites of Spring.

Because of our interest in indigenous European paganism, EarthSpirit has sought, since the beginning, to build bridges with indigenous communities from around the world, particularly with American Indians. We want to be able to understand firsthand the various issues faced by those communities, and to lend a hand if and when we can.

One particular area of concern is the wanton appropriation of indigenous spirituality by non-Indian people, including some pagans. And we also want to make them aware of the indigenous dimension of European paganism, since it is not something most people are familiar with. In 1986, we established the EarthWays Initiative as a vehicle to engage in dialogues with indigenous leaders. To date, there have been more than two-dozen such conversations with people from nine different countries.

EarthSpirit has also been involved in interfaith dialogue for a very long time. We realized early on that the interreligious community was a forum where pagans could potentially be seen and heard and accepted for who we really are.

The interreligious movement is particularly focused on eradicating prejudice and on promoting social justice, as well as understanding and respect among the world’s faiths. There are many influential religious and academic leaders who are part of that movement. We felt that, given the opportunity, if we could change a lot of perceptions regarding paganism in that setting, those changes could, in turn, wind up benefiting pagans everywhere. Deirdre and I were members of the Greater Boston Interfaith Council for most of the eighties and early nineties, and then starting in 1993, we began a long association with the Parliament of the World’s Religions.

The Parliament is the world’s oldest and largest interreligious event, originating in Chicago in 1893. It is convened approximately every five years in a different city, and draws close to 10,000 participants from just about every corner and religion of the world to spend a week attending workshops, panel discussions, ceremonies, artistic events, etc. EarthSpirit has sent a delegation to each of the modern Parliaments – in Chicago (1993), Cape Town (1999), Barcelona (2004) and Melbourne (2009), and MotherTongue has performed at three of them (the next Parliament is scheduled for Brussels, Belgium in 2014). In 2006, I was elected to the board of trustees of the Council that organizes and runs the Parliament.

An important focus of my work in the Parliaments, and in the interreligious movement in general, has been to present the European pagan traditions in the context of the indigenous cultures of the world, a case which I have tried to make in various forums since the late 1970s. Within the interfaith community, the different religions tend to be grouped under several distinct categories: Abrahamic, Asian, Indigenous, etc. Pagans are generally placed in the category of New Religious Movements, which, as the title implies, includes religions of fairly recent origin (generally those which were established after 1850).

This certainly seems to be the most appropriate designation for neopaganism, and, in principle, there is no stigma attached to such a categorization, which also includes many well-respected religions. It also, however, includes several religions which are considered to be ‘cults’ by a great many people and, given the negative baggage that pagans have had to endure, our inclusion in that category exclusively makes it easy for our detractors to engage in a little ‘guilt by association.’

In suggesting that some pagan traditions should be more properly included in the Indigenous category, I have tried not only to underscore the indigenous character of those traditions, but also to bring some balance to the way pagans are perceived in the interfaith movement, since in that movement the indigenous traditions are accorded a great deal of well-deserved respect, not only for the length of their existence, but also for the many evils they’ve had to suffer.

As you might imagine, there’s been a great deal of resistance to this idea, a lot of it coming from Christian conservatives who realize (and have told me as much) that the inclusion of paganism in the Indigenous category could give it the credibility to raise serious accusations against Christianity (and particularly the Roman Catholic Church) for its wanton slaughter and extermination of the European pagan peoples.

But not only the Christians have been resistant – many pagans have objected as well because – given how incredibly touchy the question of ‘legitimacy’ has been in the pagan movement – they fear that this would create a pagan hierarchy within the interfaith community. That has certainly never been my intention, I see it essentially as a question of two substantially different approaches to paganism, belonging in two different categories.

When the Parliament was convened in Melbourne a couple of years ago, the Indigenous traditions were a major focus of the event. I was part of the Task Force that organized the Indigenous programming, and was delighted when the other members of the Task Force decided to include the European traditions in the program. In so doing, for the first time ever a major interreligious organization finally recognized traditional European paganism as indigenous.

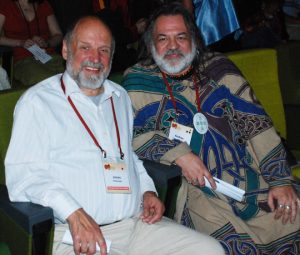

I was invited to be one of two representatives of the European traditions and, in turn, I invited krivis Jonas Trinkunas, the head priest of Romuva – the pagan religion of Lithuania – to be the other. I think it was a real eye-opener for many pagans at the Parliament to see how differently we were treated by many members of the interfaith community, once they began to wrap their heads around the concept of indigenous pagan spirituality. But the best thing of all, to me, was the very warm welcome and acceptance we received from the various indigenous delegates at the Parliament.

Christopher: Where can people learn more?

Andras: The EarthSpirit website can be found at http://www.earthspirit.com, and the e-mail address is earthspirit@earthspirit.com; there’s also a Facebook page. The postal address is P. O. Box 723,Williamsburg, MA 01096. I can be reached at aarthen9@gmail.com, and I’m also on Facebook.

[This interview with Andras Corban-Arthen is re-printed in full, with permission, from ACTION, the newsletter of the Alternate Religions Educational Network, Yule 2011].

Jonas Trinkūnas, founder of Romuva, receives award from Lithuanian President

Published July 12, 2013 by EarthSpirit Community on EarthSpirit Voices

Written by Andras Corban-Arthen

EarthSpirit recently sponsored a series of performances in Massachusetts and Vermont by Kulgrinda – the ritual performance group of Romuva, which is the name given in modern times to the revived ethnic pagan religion of Lithuania. Jonas Trinkūnas, the krivis (supreme priest) and founder of Romuva – who took part in those performances – is an old friend, someone I’ve known and respected very highly for some twenty years.

Jonas attended Rites of Spring back in the nineties, and I have visited him, his family, and his community in Lithuania. In 2008, when the Parliament of the World’s Religions put me in charge of finding representatives of the indigenous spiritual traditions of Europe to attend the upcoming Parliament in Melbourne, Jonas’ name was the first on my list.

A few days ago, on 6 July, Jonas had the distinction of receiving the prestigious Order of the Grand Duke Gediminas, one of Lithuania’s top civilian honors. The award was personally bestowed by Dalia Grybauskaitė, the president of Lithuania, who praised Jonas for his involvement with the underground resistance against the Soviet regime which ruled Lithuania for over forty years, as well as for his work in preserving traditional Lithuanian religion and literature.

Lithuania was the last country in Europe to officially become Christian – a change which took place mainly for political reasons, and which was not completed until the beginning of the 15th century. The pagan religion co-existed with Christianity for a very long time beyond that, and continued to survive even after Catholicism became dominant and gradually attempted to assimilate and eradicate the remaining pagan practices. But paganism still lived on in the countryside: a large sector of the peasantry, though nominally Catholic, kept alive their traditional pagan spiritually which was deeply ingrained in their everyday lives. A very strong folkloric movement which began in the 18th century helped to keep alive, in the urban centers, an awareness of Lithuania’s pagan roots.

Jonas Trinkūnas immersed himself from an early age in the myths and folklore of his native land, and by the time he’d finished his university studies in the early 1960s, he had published a number of articles as well as a dissertation on pre-Christian Lithuanian religion. He became a researcher and professor of literature and ancient cultures at the University of Vilnius, and during that time he founded a very popular folkloric organization which presented a variety of traditional folk music and dance events; he also began making extended visits to the countryside, to learn directly from rural villagers what still survived of the original pagan traditions.

Jonas’ activities brought him afoul of the Soviet authorities, who feared that his religious and folkloric pursuits were fomenting nationalistic sentiments which could lead to acts of sedition. He was interrogated by the KGB, and subsequently dismissed from his teaching position at the university, and forbidden from holding any kind of teaching job; for many years, he was forced to do various kinds of menial work in order to support his growing family. His folkloric organization was officially suppressed, and he could only engage in his religious practices clandestinely.

Finally, with the loosening of Soviet government controls brought about by glasnost and perestroika in the late eighties, Jonas was able to resume his public activities and to bring Romuva out in the open. Since 1990, when Lithuania achieved its independence from the Soviet Union (the first of the former Soviet republics to do so), Romuva has grown steadily and has achieved a strong presence in Lithuanian culture, though it has not yet managed to gain official government status as a traditional religion.

It may have been an unprecedented event for a pagan leader to be awarded a high honor by the president of his country – it’s certainly something that should make all pagans around the world very proud. Let us hope that the bestowal of the Order of the Grand Duke Gediminas upon Jonas Trinkūnas signals a growing willingness by the Lithuanian government to grant Romuva the official status it has long deserved.

Loving the land, leaving the land

Published May 15, 2013 by EarthSpirit Community on EarthSpirit Voices

Written by Alison Mee

Alison Mee, has been part of the EarthSpirit community since 1999. She lives near Harpers Ferry in West Virginia.

A year ago, as events in our lives unfolded, both logic and intuition told my husband and I that we needed to pick up and move our family from our home of 18 years, to somewhere new. We felt about as sure as we could be, that the move was right for us, that we were moving toward greater joy. But that didn’t make it easy for me to leave the land.

A year ago, as events in our lives unfolded, both logic and intuition told my husband and I that we needed to pick up and move our family from our home of 18 years, to somewhere new. We felt about as sure as we could be, that the move was right for us, that we were moving toward greater joy. But that didn’t make it easy for me to leave the land.

I had allowed myself to fall in love with the land on which I lived. I had connected to it as deeply as I knew how. One summer, I decided that every single solitary day, I would eat something from my land. I started with the chives and the fresh onion grass of spring. Then, with my relatively meager gardening skills, I grew some vegetables, and brought snap peas with me when I traveled, keeping them carefully and eating one every day. By autumn’s figs, I was feeling the land as part of myself.

I went through retreats, of staying on that land for a week or so at a time, spending time outdoors, but not going beyond that piece of land. I composted the story of my life, into the soil: apple wood from the home where I grew up, branches from the woods behind my grandmother’s house, flowers from funerals and weddings. The first time we placed each of my children’s feet on the earth, it was there. I brought bits of the land — soil, moss, pine needles — with me when away from home.

How could I leave? I could leave, I found, with love, appreciation, and intention.

As soon as we knew we were going to be selling the property, we had a family ritual with the land. We thanked it for it’s support of our family, and rejoiced in all the great years we’ve had there. Then, I opened up the thicket, the space that I had set aside some years ago to be mostly free from human intervention. I wouldn’t be protecting it in the same way anymore. Our relationship would be changing.

Then I sought to use my connection to the spirit of the land where I had been living, including the local river, to reach out to the land I was moving to, to help me find my correct path. Somewhere, I knew, was a place that could give me what I was needing, and likewise, could need me. I wanted to let the land reach out to me, as I searched for it.

When we were looking for our new home, I paid as much attention to the land as I did to the houses. We explored all over the county, and I smelled the dirt. At first I was shy and kept trying to do it when the realtor wasn’t looking, but eventually I got used to his attentiveness and he got used to the fact that I spent more time on the land than in the house. I stopped worrying about his opinion of me. Finding the right land was more important to me than not weirding out the realtor.

If I weren’t going by smell, I’ve since learned that I could have gone by field guide maps. It turns out that what smelled so good to me was biodiversity. Where we live now has a huge variety of plants and animals.

Now that I’m here, I’m falling in love again. Instead of plowing in with what I think should be here, I’m waiting and letting the woods show me their paths. I’m watching to see what’s going on. Who has been living here before me? What needs to be done? What’s been waiting for me? What would rather be left alone?

I bring water from my old home, to my new home. And earth. And sap from the white pine which used to be my meditation spot. If I were moving very far, I might worry about bringing non-indigenous plants, insects or microorganisms. But it would still be acceptable, generally, to bring vegetables grown in one home, and then compost them into the land in the new home. And in this way I’m bringing the story of my life forward, weaving together the connections.

Now it is spring, and I am seeing the emergence of new flowers, hearing new birds, connecting deeper with the spirit of this land.

And tasting the sweetest onion grass in the world. I’m home again.

On music and roots

Published July 7, 2013 by EarthSpirit Community on EarthSpirit Voices

Written by Deirdre Pulgram Arthen

This past weekend I attended the Old Songs Festival just outside of Albany, NY, as I have done for all but two of the last dozen years. It is a place that feeds my soul. I get to dance and sing, listen to and play music — and relax, with no performance expectations from anyone. The musicians who come there are, for the most part, people who feel the roots of their music: they study their traditions in great depth and absorb them into their bodies, then exude them in their playing and singing. Their motivation is love — not fame or fortune, but love of music, love of the old ways themselves, love of the people who brought the traditions into being and of those people who carried them on, love of harmony, love of community, love of our species, love of the earth. Many of the people who perform, organize, and attend have deep and long-held commitments to social justice and to the environment. Many have been political activists for decades. Very few preach. Instead we bask the joy of making music together as we walk through the fairgrounds and feel the satisfaction found in sharing the work of making the world a better place.

While there were many things that I loved that weekend, there was a song that Gordon Bok performed that especially touched me. It was something that he had written years ago as a result of listening to the marine radio channel in Maine, which he said he does for entertainment sometimes. It was essentially a conversation between two lobster fishermen. One was stuck and, over the course of the song, the other one came to help. That was it, really. But something in the way that Gordon captured all of us in the fairly common conversation of two men on the water was just magic to me. There they were, fishermen on the ocean – that vast and moving body of water that cares nothing for people, but still feeds us and gives us life. And here we all are, humans in a universe that is not centered on our needs and desires, but which we must live in and depend on while we are incarnate beings. We can forget sometimes that we are also floating – maybe near the rocks, maybe out of our depth – and that the simple act of accepting an offer of help allows both us and our neighbors to experience ourselves more fully as the interconnected beings that we are. The song held the magic of knowing, and Gordon shared that knowing with us all.

I find my own path reflected in that community of music makers. I, too, value the roots of my traditions and those who have brought them forward, and I find in the shared songs and dances true expressions of the joy of being human, fully intertwined with all that is creation.

My First Handfasting

Published March 28, 2013 by EarthSpirit Community on EarthSpirit Voices

Written by Andras Corban Arthen

Exactly 40 years ago, in 1973, I performed my very first handfasting. I had originally learned about this traditional European marriage ceremony from my teachers, who had told me about handfastings (or “left-handed marriages,” as they were sometimes called) in Scotland, how they differed from Christian nuptials in both concept and form, and how they were still clandestinely practiced by some in Gaelic-speaking communities in the Highlands. And I had recently attended two such ceremonies, the religious weddings of pagan friends who subsequently legalized their marriages before a justice of the peace. The possibility that I might be called upon to officiate a handfasting any time soon, however, had not even crossed my mind.

Exactly 40 years ago, in 1973, I performed my very first handfasting. I had originally learned about this traditional European marriage ceremony from my teachers, who had told me about handfastings (or “left-handed marriages,” as they were sometimes called) in Scotland, how they differed from Christian nuptials in both concept and form, and how they were still clandestinely practiced by some in Gaelic-speaking communities in the Highlands. And I had recently attended two such ceremonies, the religious weddings of pagan friends who subsequently legalized their marriages before a justice of the peace. The possibility that I might be called upon to officiate a handfasting any time soon, however, had not even crossed my mind.

Ginny was a friend from work. She had been assigned to show me around the library on my first day there, and we had taken an immediate liking to each other. We were about the same age, had a very similar sense of humor, and quickly discovered that we shared the same political views about some of the important causes of the day – the Civil Rights movement, Women’s Liberation, Gay Liberation, and, of course, the Vietnam War. And, certainly not least, we were both diehard Red Sox fans.

Ginny was very blunt-spoken, and readily used four-letter words, a habit for which she had been reprimanded by her boss a few times. There was something very “tomboyish” about her, and I remember her telling me that one of the reasons she had applied for her job was that she wouldn’t have to wear a dress to work every day.

We started having lunch together frequently, and once in a while would go for a couple of beers after work. As we became closer, I eventually felt enough trust to confide in her about my being pagan; she thought it was odd, but interesting, and the subject would occasionally come up in our conversations.

One day, as we got together for drinks after work, we were joined by Betsy, Ginny’s roommate of several years. Ginny and Betsy had become friends in high school and attended the same college, where they originally began living together, and had continued doing so after graduation. It turned out that Ginny had told her roommate about my paganism, and Betsy had become very interested and wanted to meet me to talk about it.

Betsy and I hit it off as quickly as Ginny and I had, and we enjoyed a very pleasant but brief conversation because of time constraints. Ginny suggested that I have dinner with them at their place the following week, so we could talk some more; she mentioned that I’d be in for a treat, since Betsy was a wonderful cook.

That certainly proved to be the case, and as we talked about paganism after dinner in their tidy, plant-filled North Cambridge apartment, the two of them sat on the sofa opposite me. At some point, Ginny matter-of-factly reached over and pulled Betsy close to her, and we continued talking as the two of them snuggled on the couch. A little later, during a lull in the conversation, they casually kissed.

While that might not raise too many eyebrows nowadays, back then it was a very different story – people of the same sex simply didn’t engage in open displays of romantic affection toward each other. At that point in my life, the only times I had ever seen two women kiss on the lips were in a couple of European art films, but never in the flesh. I imagine, in retrospect, that if I had watched two women I didn’t know kissing like that in public, I might have felt somewhat uncomfortable; for all my avowed support of Gay Liberation in principle, I really didn’t have much actual experience with gay people.

But I knew Betsy and Ginny, and it was very obvious that they shared a very deep bond of love, friendship and affection, so their intimacies didn’t faze me at all – they felt natural, normal, right. If anything, I was glad that they were comfortable enough to be themselves around me.

They came out to me then, and we spent the rest of the evening talking about their lives, their love for and bond with each other, the struggles they’d had to face dealing with family and friends, and those they kept encountering with neighbors and at work.

And we talked about the pain – the pain of rejection and marginalization, of not being accepted for who they were; the pain caused by prejudice, by discrimination, by not being able to marry and live normal lives like most people; the pain of having to deny and hide their beautiful love every day of their lives. Tears flowed, we held each other, and from that moment became a lot closer; over time, I came to experience even more the depth of their love for one another, the strength of their commitment.

Months later, Ginny and Betsy told me that they had decided to get married. They knew there was no way they could legally do so, but they wanted, at the very least, to have some sort of unofficial ceremony, some spiritual affirmation and blessing of their relationship. They approached the minister of one of their family’s churches, but he turned them down. Over the next few months they tried churches of other denominations, only to meet with similar results.

They eventually pinned their hopes on the minister of a local Unitarian-Universalist congregation, someone they’d met at a friend’s wedding; they suspected he was gay, and felt that he, of all people, might be willing to marry them. He turned out, in fact, to be very sympathetic, but also apologetic – he wished he could perform the ceremony, he’d told them, but he was too afraid of losing his job if word ever got out. They were heartbroken.

Then, one day, Betsy showed up at my library at the time I usually went on coffee break, and asked if she could talk to me. She had just remembered my telling her about the pagan handfastings I’d attended, and a light bulb had gone off in her head. Could I – would I – perform a handfasting for them? She took me completely by surprise: the thought had not even occurred to me, as it obviously hadn’t to them until that moment.

After regaining my composure, I had to think a bit – I was just in my early twenties, and had only been on my path for four years, so what she was asking was a bit daunting. I finally told her that I could not remember anything in all my training that raised objections to the marriage of two people who clearly were in love and wanted to ceremonialize their commitment to each other.

And so it was that on a gloriously sunny but chilly spring morning, a small group of us gathered in a secluded part of a large public park in Brookline, surrounded by pines, to celebrate the handfasting of my two friends. It was a bittersweet event: Ginny’s mother was there, as were two of Betsy’s sisters; the rest of their families had adamantly refused to attend. Just a few close friends completed the party, twelve to fifteen people altogether, but what we lacked in size, we more than made up for in spirit.

We blessed them with mead. We blessed them with rose petals. I took the multi-colored cord they had brought and wrapped it around their joined hands. They each tied a knot while saying their vows to one another, looking deeply into each other’s eyes, the smiles on their faces more radiant than the sun. I tied the third knot on behalf of their family and friends, and pronounced them handfasted in marriage.

As the rest of us offered them our good wishes for their life ahead, I remember hoping that, one day, they would be able to renew those vows in a ceremony that would finally legitimize the marriage which took place that day; not because some legal piece of paper would make their relationship any more meaningful or real, but simply because the love which they had for each other deserved to be untainted – in any way at all – from ever being considered second-class.

I lost track of my two friends over the years, but they have been very present in my mind lately, as the U.S. Supreme Court begins to hear arguments regarding two cases that could decide the future of same-sex marriage in this country. Let us hope that the justices will put aside political and religious ideology, and rule in favor of freedom and equality under the law.

The measure of freedom lies in the ability to make choices; and whom we decide to love and share the rest of our lives with, is one of the most important choices we can ever make. In a truly free society, everyone should be able to make that choice equally, with equal rights and responsibilities – whether we choose someone of a different race or religion, or of the same sex; or whether we choose to share our lives with one other person, or with several.

I am proud to live in Massachusetts, where same-sex marriages have been legal for almost a decade, the first state in the Union to take such a step. As I think of Ginny and Betsy, I can’t help but wonder if they stayed together living here throughout all these years.

I’d like to imagine that they did, and that they stood in line at the courthouse in 2004 to be among the first to take advantage of the changed law, to finally legalize their marriage. And I’d like to imagine them now, two older women sitting close to each other on the couch at their home, tightly clasping their ring-bedecked hands while gazing fondly at the thin, multicolored cord hanging over their front door, the cord that we bound together forty years ago.

Offerings

Published May 18, 2012 by EarthSpirit Community on EarthSpirit Voices

Written by Katie Birdi

The world is (among other things) a cycle of give and take. We breathe out, the plants breathe in. The plants breathe out, we breathe in. Offering doesn’t have to be about sacrifice. It can be joyful gratitude for the bounty we are surrounded by, a connection with our prayers, a gift of service, and the passion we are compelled to express.

The world is (among other things) a cycle of give and take. We breathe out, the plants breathe in. The plants breathe out, we breathe in. Offering doesn’t have to be about sacrifice. It can be joyful gratitude for the bounty we are surrounded by, a connection with our prayers, a gift of service, and the passion we are compelled to express.

My offerings come in cycles, as a part of my daily practice. I offer something daily, weekly, monthly… and they connect me to different rhythms in my life. Daily, I offer my breath to the plants, keenly aware that their existence, and my own, is locked in an elegant (covalent) bond. Weekly, I offer a bowl of rice to the spirits of the land I live on in respect and gratitude for the Unseen Ones that populate this place with me. Monthly, I donate newborn and preemie hats (knitted with love) to the local hospital. Every other month, I also head downstairs to donate a pint of my blood, a very physical offering, and one of my favorites. I give thanks that I am healthy and strong, watching my blood flow out of my body, and wish with each drop that whoever receives my blood also be healthy and strong. I do my best to stay open and aware, and I give other offerings as they seem appropriate. I do my best to do it with a clean, clear heart, and with respect and honor to the world which is my home and family. One of my favorites is to leave nuts in the holes of trees. I will do this to give thanks, sometimes in supplication, and sometimes just because it feels right to do.

Offerings come in many forms. Gifts of service are particularly humbling to me. I have friends who host gatherings, musical performances, and I have one friend who consistently does the dishes after a group meal. What an amazing, oft overlooked offering! I am touched each time a person holds the door for me, offers water to a dog that needs it, chooses to ride a bike instead of drive a car, or offers to help someone change a flat tire. Recognizing these offerings makes each moment of my life sweeter.

My son turned two in February of this year, and we enjoy frequent walks in the woods. I am so glad to have the opportunity to show him all the wonders that the world so passionately expresses. I was dismayed at first, that my son was most fascinated by the trash he would find in the forest. Running past a snail, a fallen tree, a pine cone and a forest of fiddleheads, he triumphantly points his finger at a smashed plastic cup and its blue straw, sticking up pathetically from the wreckage. “Bwoo! Bwoo!” he says, looking for affirmation that he has correctly identified the color of this amazing thing he’s found in the forest. “Yes, blue” I say, proud that my son is developing in language, awareness, and ability. I’m also dismayed that the forest I’ve brought my son to, hoping to teach him about the sacredness of the Earth, is filled with trash.

It occurs to me that the trash I’m surrounded by is an offering. The people who have left these offerings have shown, with their actions, how much they value the Body of the Earth. What are you offering? Is it the best of who you are and what you have to give? If offerings are a prayer, what are you praying with? What sorts of unspoken things are you saying to the world and your community with your habits? If the only offerings we make are the convenient offerings of coffee cups, wasted food, and misprinted copies, we invite similar energy into our lives. Take a moment. Take a breath. Take only what you need, and give of yourself in return.

I do my best to help my son learn the vital lesson of the Thank You letter. Gratitude is something I wish to nurture in his nature. I do my best to teach him that an Intentional Offering isn’t always a thing. Sometimes it’s money, food or goods, but sometimes it’s an offering of time, skill, or consideration. Sometimes it means inconveniencing ourselves for the good of the World. Carry a reusable water bottle. Enjoy your reusable mug. What do you “throw away” on a daily basis? Where does it really go?

When we go shopping, my son has his own, toddler-sized reusable shopping bag, and his own toddler-sized water bottle. Children learn by imitating adult behavior, and as Mama carries a reusable bottle & shopping bags (offerings of consideration), he needs one of his own. One of his first chores was to help Mama sort the recycling. We talk about reducing, reusing, and recycling every day. The concepts are clearer to him now than the words are when he says them, and I am a Proud Mama…and now our walks in the woods include a bag for the trash we find, which we sort for recycling later.

a safe home for antelope

Continuing from previous post the future of my people’s musical traditions, developing a captive breeding program for antelope in Kopeyia might be a way to help retain Ewe musical traditions. “Hey, how hard can it be?”

Since then, the three of us have worked to bring this program to life. After Emmanuel returned to Ghana, he identified some land adjacent to the Center on which the facility could be built and engaged the participation of a friend, a man named Christian, with construction experience to act as general contractor for the facility. Christian lives in the city of Ho, which lies about two hours north of Kopeyia and is in the region where hunters can still find antelope, so he also began the task of developing contacts within the community of hunters there, which we would rely on in the months to come.

Since then, the three of us have worked to bring this program to life. After Emmanuel returned to Ghana, he identified some land adjacent to the Center on which the facility could be built and engaged the participation of a friend, a man named Christian, with construction experience to act as general contractor for the facility. Christian lives in the city of Ho, which lies about two hours north of Kopeyia and is in the region where hunters can still find antelope, so he also began the task of developing contacts within the community of hunters there, which we would rely on in the months to come.

Joss and I, for our parts, began to raise the funds necessary to begin the construction as well as to do the necessary research on the antelope themselves, particularly on their breeding behavior and husbandry needs. Joss produced a video about the project, which we used to raise the first round of funding through Kickstarter, a web-based service that allows people with ideas for creative projects to reach out to others who are interested in supporting worthy causes. Many of you reading this now are among the almost 100 people who contributed to the project, called “To Make the Drums Sing.” We raised almost $4,000, which went entirely to support the initial phases of construction. (You can still see the video on the Kickstarter site, although it is now closed to contributions.)

I spent my time trying to learn everything I could about antelope and captive breeding. I found myself at a bit of a disadvantage in this because my professional experience has been largely focused on wildlife in North America, and I don’t have any previous field experience with the species involved. I was confident that domestication and captive breeding of antelope would be possible; not only had others done this successfully with some species, but antelope are in the same group of mammals (the family Bovidae) that include goats, sheep, and cattle, which are perhaps the most successful forms of domestic livestock in the world.

But even though it was possible, it was also possible to do it wrong. I knew that we wouldn’t have the money for long-term experimentation; we needed to start the project with as much information as we possibly could.

Language proved to be a major barrier. Emmanuel and Christian could only express their knowledge of what species we wanted to raise in Ewe. My ability to review the published literature and seek advice from zoo professionals required that I know the species names in English or their Latin genus-species binomials. It took several months of emails and phone calls throughout North America and Africa to find a wildlife biologist with enough fluency in both English and Ewe to help us make the translations. (It later turned out that, even then, the translations were not entirely accurate, but at least I had somewhere to begin.)

In early December, Joss and I finally left for Kopeyia to start the construction of the facility and the collection of the antelope. Bearing the fruits of our fundraising and research efforts, we arrived near the start of the dry season, a short window of time during which construction would not be hampered by rains and the antelope would be (relatively) easy to catch. There was no time to waste.

During the month that we were there and the following month after we had to return to the U.S., the project moved forward out of its purely conceptual phase. Several threads to the project were launched almost simultaneously, each of which was an integral part of the whole.

- A mason was hired to construct several hundred concrete blocks, approximately 16 x 8 x 4 inches. The blocks were constructed on-site, in Emmanuel’s family compound for extra security, which required the delivery of truck loads of sand, bags of cement, and the corralling of several workman whose services were in great demand throughout the rapidly developing region.

- The trenches for the facility’s foundation, 100 by 100 feet square, were cleared and excavated to a depth of about 16 inches. Through brick hard clay. By hand. With old and less-than-optimal picks, shovels, and axes. Primarily by the drumming teachers at the Center. Needless to say, this took us several days.

- The cement blocks were transported from the compound out to the construction site (again, by hand, but this time by the member’s of the local school’s soccer team) and laid to build a foundation three blocks high. Nine-foot lengths of galvanized pipe were then embedded in the foundation to serve as the upright supports for chain link fence that, together with razor wire for security and palm fronds for privacy, created the facility’s walls.

- A 40-foot deep, 8-inch wide well was dug and outfitted with a pump to provide a constant source of freshwater to the antelope. To ensure the security of the pump, which had to be imported at some expense from Togo, the well was dug inside Emmanuel’s compound. The well was dug (you guessed it) by hand. It took two men six days to auger down through the clay, using connected 10-foot lengths of pipe to drill down to the water table. A trench then had to be dug to pipe the water from the well out to a concrete water hole constructed in the antelope facility.

- A hunters’ cooperative was formed based in the city of Ho. As you might imagine, hunting is traditionally (a) a solitary activity, taking place within traditional hunting grounds that are exclusive and hereditary for each hunter, and (b) oriented toward the killing of the animals. We were asking the hunters to do something entirely new; we wanted them to capture the antelope alive and in healthy condition. Because this would require the use of a very large net (which we created from a used fishing net, 180 x 12 feet), no single hunter would be able to handle the operation on his own. To be successful, they would need to work together, cooperatively deciding when and where to work, how to manage the net, and how to share the profits.

The facility is now finished, complete with shelters and landscaping. And on February 16th, the first antelope, a baby bushbuck, was introduced into it. Emmanuel named her Dzidefo, which in Ewe means “confidence.” Since then, a few other antelope have joined her, all feeding on cast-off plant material from farm fields, such as cassava leaves and coconut husks, which are known to be favored foods.

The facility is now finished, complete with shelters and landscaping. And on February 16th, the first antelope, a baby bushbuck, was introduced into it. Emmanuel named her Dzidefo, which in Ewe means “confidence.” Since then, a few other antelope have joined her, all feeding on cast-off plant material from farm fields, such as cassava leaves and coconut husks, which are known to be favored foods.The spark that was originally ignited is now a small flame.

Much remains to be done, of course. More antelope need to be added to the program. It has proven harder to capture a critical number of the Maxwell’s duiker, the species that we think will be the easiest to raise and breed. Time still remains in the dry season to meet our target for the year, so efforts at capture continue. We also need to secure on-going funding to hire permanent staff for care and security. In addition, the regional paramount chief, Torgbui Fitsi, has asked us to consider ways to develop an educational program that will link the facility with the public schools in the region.

All of this will require financial support, of course, so to increase our ability to raise funds through both public and private sources, we are now in the process of incorporating “The Ghana Antelope Project” as a non-profit organization with the ultimate goal of securing 501(c)3 tax-exempt status with the IRS.

Once that happens, we’ll see just how far this fire can spread.

Hey, how hard can it be?